This started out as another 13th Age post, but I ended up tabling it as a bigger issue came up in discussion which, I think, crystallized a few thoughts about games, how they’re run and how they’re played.

Now, here’s the caveat up front: I’m speaking in broad generalizations here, not making assertions about anyone’s experience.

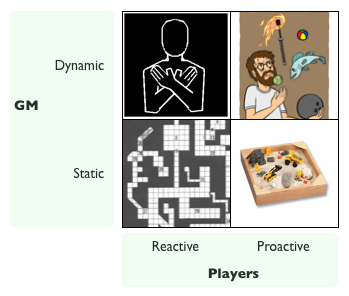

Ok, so with that out of the way, I have been thinking a bit about some of the divergence in assumptions that emerges over time with play. When we start out, there’s often a lot of similarity, if only because there’s a certain commonality to inexperience. As GM’s, we stick to the script, and as players we take our cues from what’s going on and try not to push things further until we are a lot more comfortable with all these weird lines and numbers. Speaking broadly, the GM is offering static content and players are largely reactive.[1]

This is, assuming everyone is well intentioned, a very safe space to play in. It’s a great opportunity for both sides to learn the ropes, and with time, it allows the group to start pushing boundaries that interest them (whether mechanical, narrative or otherwise). It also suits fairly constrained play, whether that’s a dungeon crawl or an adventure on rails.

Now, if the GM starts getting a little bit more dynamic in her gameplay, things shift. Functionally, this is the point where NPCs stop having scripts and start having agendas, and their interplay and actions provide a backdrop for play. Even if players are still reactive, they have a lot more that they can react to, and they can forge alliances, foil plots and generally make heroic nuisances of themselves. This is good fun, and it really makes a world feel more alive because there are clear reactions to player actions.

This also ends up being very useful for larger games (including many LARPS) because agendas are easier to play and communicate than bombarding people with raw data. However, this also highlights a potential weakness of this approach – it’s not hard for it to turn into a puppet show, where players just get to watch cool people do cool things.

In the other direction, if the GM still pretty much just responds to the player’s needs but the player’s start taking the bull by the horns and deciding what they want to do and how they’re going to go about it, the nature of play changes similarly. The GM is no longer plopping adventures in front of the players, and instead play is emerging naturally from the things the players are trying to do.[2] This is also pretty awesome because, presumably, the players are interested in what it is they’re doing.[3]

And, of course, if you have both a dynamic setting and proactive players, then it’s pretty much non-stop action, provided you can keep all the balls in the air.

Ok, so this is all well and good, but I want to call something out here: the purpose of this map is not to suggest some sort of path of improvement or Gartner style best performers. Each quadrant of this offers the opportunity for awesome (or crappy) play, and the boundaries between them get absolutely fuzzy. The purpose of these quadrants is not to suggest that you should seek your fun elsewhere, but rather, to offer insight on where other people find their fun.

Why is this important? I occasionally talk to GMs who are running good games who wonder if they’re doing something wrong because they’re not doing X or Y. Usually, X or Y is something that totally works in another quadrant, and which will only bring them pain if they try it as is (or leads to “we tried it and it sucked” stories). The quadrants hopefully can remind a GM that they want to solve their problems, not someone else’s (and maybe illustrate why someone else is having fun with something you’d never enjoy).

Now, yes, obviously, there’s also the element that if your current quadrant isn’t working for you, it’s good to know that others exist in case you’re looking for direction for other things to try. But it’s important to note that this is the difference between understanding the options and evangelizing one option over another.

I’ve played in all 4 quadrants, and I’ve had an awesome time in each one (sometimes within the same game). I’m very resistant to static/reactive unless I know that’s the deal going in, at which point I’ll buy in whole hog. Dynamic/reactive requires a lot of trust on my part, but I love it when it works. Static/proactive allows for great games, but its often more work than I’m really inclined towards as player a lot of the time. Dynamic/Proactive is awesome, but tricky to sustain. All of which is to underscore – this is not a grading system, it’s just a way to maybe get a grasp on what other people enjoy rocking out to.

1 – While this was the historical entry point for RPGs, that’s no longer a safe assumption. Nowadays, there’s a lot of entry from other corners, especially the upper left. Mostly, that just underscores that there’s no right progression through this, it’s just a yardstick for taste. But it also tends to assume a novice entering an experienced group, which has always been a vector of entry. Obviously, if a player enters with a existing group, they’ll be drawn to whatever space that group occupies. The lower left is a natural direction if no one has experience.

2 – This illustrates one particular subtlety about sandbox play – letting players do anything is easy. Letting players do anything and making sure it stays interesting takes work.

3 – Additional bit of fun – this quadrant contains a lot of narrative games as well as hard core old school sandbox play. The commonality is that players are the ones calling the tune.

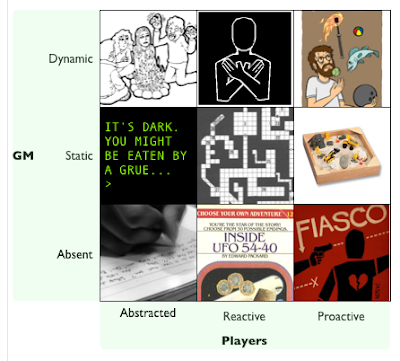

BONUS

Sometime after I finished this post, I ended up expanding the diagram into a 3×3 beast, which I now present without comment: